In July I went to an event as part of Porty Pride, where Ashley Douglas discussed her work and her part in researching the poetry and life of Marie Maitland; a woman who lived just outside of Edinburgh in the 16th Century, wrote lesbian poetry and was described by her contemporaries as ‘Scotland’s Sappho’. I quickly became fascinated by Marie, and by Ashley’s work to uncover, share and raise awareness of Marie’s work and improve the understanding of Scottish LGBTQ+ history as a whole, and so I was delighted that Ashley agreed to sit down with me to discuss this.

Ashley is a multi-lingual researcher, writer, translator, consultant and speaker. She is also a specialist in the Scots language and in LGBTQ+ history.

Her work as a researcher and historian of Scots language led her to a manuscript that had been previously written about by several scholars, containing poetry by a range of famous sixteenth century men, including Marie’s father and King James VI. But while Ashley was reading the manuscript, she noticed something that surprised her.

“I found out about [Marie] quite by accident. The many technically anonymous, but female-authored, poems of the manuscript have been overlooked or undermined by scholars for centuries, and up to the present day. I was studying the manuscript as a record of Scots language history, and was surprised and overwhelmed to find myself reading an explicitly lesbian love poem, written in the 1500s, that I had never heard about before.

“It should be famous, as should Marie – who lived two centuries earlier than the now-iconic Anne Lister – but homophobia and misogyny has kept this precious primary record of LGBTQ+ history from us until now.

“It is a sad reflection of the heteronormativity, at best, homophobia, at worst, of society and academia that it has taken a lesbian woman, in the 2020s, to finally read, see and celebrate Marie’s poetry for what it is: an astonishingly early and powerful primary record of lesbian love in post-Reformation Scotland. The heteronormative – at best – academic resistance to reading Marie’s poem for what it is has been an important, if regrettable, part of its story.”

There are several reasons that academics had so far failed to recognise Marie’s work. Some academics have viewed ‘Poem 49’, one of the poems in the manuscript, as a friendship poem between two women. If you read the poem, it is quite clear that this is not true. Other academics have postured the idea that the poem is written by a man from a woman’s point of view.

There are three sapphic poems in the manuscript, out of 95. Of these 95, a third of the poems are anonymous, and so likely written by women. These poems have been overlooked and ignored by scholars and academics.

It isn’t just the academic and the historical side of Marie’s work that is important. Sharing and raising awareness of LGBTQ+ historical figures shows LGBTQ+ people today that they have always been around.

“Gay people have always existed, even at times when homophobia was far worse than it is today. Marie is a shining example of that. For gay people, seeing ourselves reflected in history, knowing that people like us have always existed, makes us feel valid and included. It makes us feel pride rather than shame, which is born of feeling invalid and alone. Telling LGBTQ+ history is as much about doing justice to those who lived in the past as it is about including and validating LGBTQ+ people today.

“Given the severe persecution of LGBTQ+ people throughout most of Scotland’s history, it is unsurprising that traces of our lives – especially positive traces, in our own voices – are often hard to find. Absence of queer evidence is not evidence of queer absence. Equally, this also means that where we do have rare records of LGBTQ+ history, we must recognise and celebrate them all the more.

“In its own context, Marie’s poetry is precious primary evidence of a woman who loved other women in 1500s Scotland. In the centuries since Marie wrote it, the history of its reception in academia is emblematic both of how LGBTQ+ history is ignored, erased and denied, and of the heteronormativity and homophobia we are still fighting against today.

“Marie is both a central figure of Scotland’s LGBTQ+ history, and a key example of how that history has been erased and kept from us.”

Work such as what Ashley has done is often described as ‘queering’ history. Ashley says “reading poem 49 as a lesbian poem is not queering history, it’s just reading it as it is. I’m removing the homophobic veil, not coming along with a rainbow magnifying glass.”

“If you think you’re reading something queer, don’t doubt yourself. Just because no academic has suggested it before, don’t assume you’re wrong. It’s not even new things being discovered, it’s just seeing things with new eyes.”

As part of Ashley’s research, she has worked on adapting Marie’s work to teach in schools. Scotland was, and remains, the first country in the world to embed LGBTQ+ inclusive education across the curriculum. Shortly after Ashley published her first piece of work about Marie, for LGBTQ+ History Month, February 2021, she was asked by the charity Time for Inclusive Education (TIE) to collaborate with them to create lesson plans for Scottish secondary schools, something she describes as a “professional and personal honour”.

“I provided all the historical and literary content, and TIE used their expertise to transform it into lesson plans tailored to Scotland’s school curriculum. One lesson plan is focused on literary analysis of the poem and its themes; another lesson plan focuses on the poem in its historical context, focusing on gender and sexuality in Early Modern Scotland.

“I am also very excited to share that I continue to work with TIE and that we have new LGBTQ+ inclusive resources launching later this year, including new content relating to Marie and Poem 49.

“LGBTQ+ inclusive education is important for the same reason that it is important to tell LGBTQ+ history generally: so that all children see themselves reflected in their learning, thus ensuring that LGBTQ+ children feel valid, accepted and included – and that others see them that way, too.

“In short, it is about preventing gay kids from hating themselves, and other kids from hating them – creating instead an environment of inclusion, diversity and acceptance.”

Ashley also worked with an artist to create an imagining of what Marie might have looked like, based on her two brothers. This painting is in the National Portrait Gallery and has been used in the educational materials, meaning that Marie is now, as Ashley says, “literally a poster girl for LGBTQ+ history across Scotland.”

Marie’s poetry was all written in Scots, which was normal for the time, as Scots was the language of the Scottish kingdom. Since then, due to all sorts of political and social factors, Scots has become minoritised and displaced by English in formal and official settings.

“Today, Scots is often wrongly viewed as “bad English”, “slang” or a “dialect”, as opposed to the language in its own right that it is. Modern Scots is the modern version of early modern Scots in which Marie lived and wrote,” Ashley says:

“We cannot tell Scotland’s story without LGBTQ+ people, and we also can’t tell it without the Scots language. Centuries of Scotland’s history took place in, and were recorded in, Scots; and it remains a living language of Scotland today.”

“As well as connecting LGBTQ+ people with their history, Marie’s poetry, and all sorts of other documents from the era in which she lived, which were also recorded in early modern Scots, also connects modern Scots speakers with their history – showing them that what they speak today is a language with a long-standing and proud history.”

Ashley also spoke to me about the personal impact and importance her research has to her, saying that she is “50% driven by fury and 50% driven by love”. She describes the situation as being “life and death”, especially when it comes to having an inclusive education in schools.

Marie Maitland and her poetry is important for so many areas of history; Scottish history, women’s history, LGBTQ+ history, but also for the way sharing her history can make people feel less alone.

As Ashley said: “Telling LGBTQ+ history is as much about doing justice to those who lived in the past as it is about including and validating LGBTQ+ people today.”

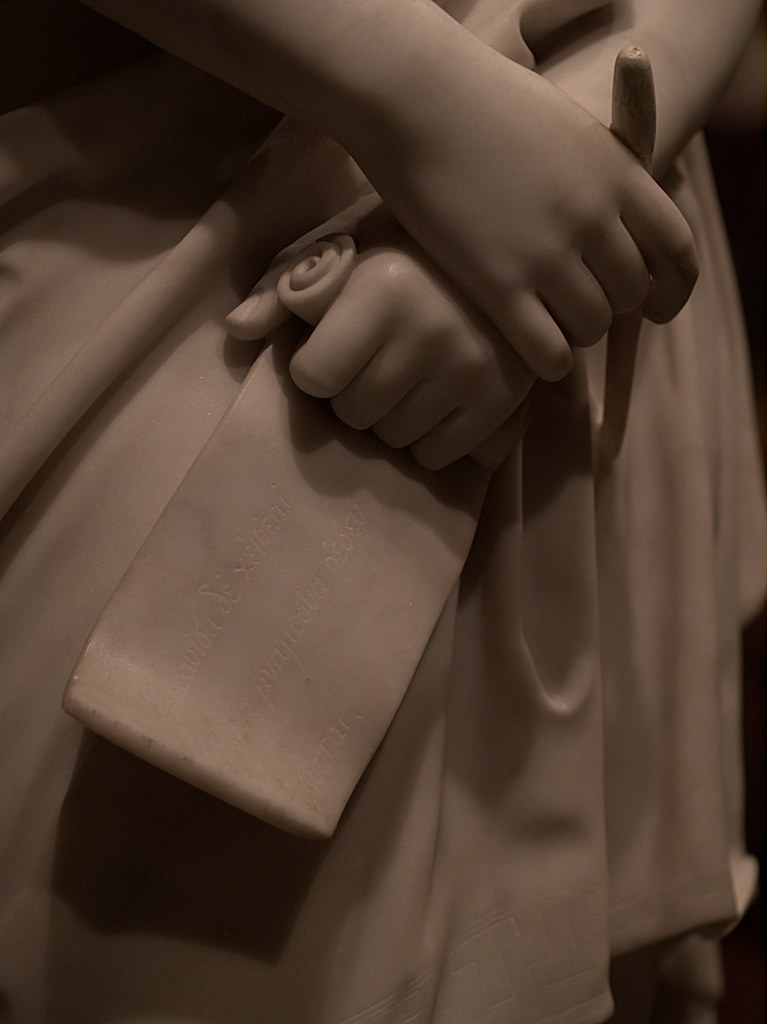

“Sappho’s Stylus & Papyrus (Washington, DC)” by takomabibelot is marked with CC0 1.0.