This month, China celebrated 10 years since the beginning of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a development program which has seen China lend an approximate $1 trillion to finance infrastructure investments across the world, especially in developing countries. The project was intended to create a ‘new Silk Road’, with the initial largest aim being to build a railway line from China to Europe which could transport goods more efficiently. The reality of the program has been slightly different: the BRI could look like a high-speed railway in Malaysia or a dam in Ecuador. It is close to home, with Ireland and Spain considering formally joining the BRI’s 154 members (apparently, Irish dance is hugely popular in China).

The BRI has attracted a wide spectrum of responses, from outrage, to scepticism, to fervent praise. But ten years after President Xi Jinping launched the program, do its results fulfil its aims?

Criticism – even paranoia – comes from China supposedly creating a sphere of political influence. It is a strategy that was seen in the American Marshall Plan beginning in 1948: regarding economic prosperity, China’s position is similar to post-World War Two America. Commentators thereby speculate that the BRI must have an ulterior ideological motive too.

But the memory of post-war diplomacy, dominated by what some would describe as informal imperialism, is still recent and is something developing countries have grown cautious of. These countries are looking for a source of money with fewer strings attached than the options provided by the IMF and the World Bank. Furthermore, an important psychological factor is that for a developing country to accept help from their former coloniser feels almost regressive. Many do not want to copy Western institutions. The Beijing Consensus – China’s political and economic policies – provides an alternative to the Washington model.

Nonetheless, valid concerns with the BRI have surfaced. The first regards economic payoff: infrastructure investment is a volatile sector with long-term reward, which seems to be incompatible with the intensely short-term focus of Chinese economic policy aimed almost entirely at maintaining low unemployment. Between 2019 and 2022, the Chinese government was paying out $104bn in bailouts, largely from investment in vanity projects. These yield negligible returns – take the 2017 Addis Ababa-Djibouti railway, which lacks both staff and passengers and has amounted $1bn in losses. Amidst thousands of successful BRI projects stands a herd of white elephants.

Recipient countries undertake projects which are not economically viable, and fall into a debt trap where returns are so far in the future that countries wonder whether their debt can be absolved at all. And with each erroneous investment, the BRI loses more credibility. China’s salami-slicing strategy is extremely myopic.

An aspect of this is mismanagement – China lacks a central department or commission to control BRI projects, distribute finances, and enforce rules or guidelines in an orderly manner. The Belt and Road Construction Leadership Group is the closest body they have in place: a small informal group within the Chinese political system reporting directly to the State Council. Some claim that a commission specialising in BRI affairs would be better placed to consider economic viability.

Indebtedness is not purely economic, as China could also leverage relationships to a military dimension. Though no Chinese push has constituted a casus bello as of yet, their ownership of ports across the world is worth being wary of. Xi’s foot in the Mediterranean door thanks to Chinese ownership of the Port of Piraeus; in South Asia, China’s $47 billion investment in Pakistan (compounded by initiatives in Tibet, Nepal, and Bhutan) could cause an upset along the Line of Actual Control or in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir; and the implications for China sourcing allies were Taiwan to be invaded is unnerving to speculate.

Finally, the environmental impact. China has been leading the shift away from fossil fuels towards renewable energy sources in the last decade, and is the world’s biggest manufacturer of solar panels, wind turbines, and clean energy technologies. In providing recipient countries the tools to develop, that these tools are green could change, even save, the future of the planet. However, mismanagement means local advisors are not employed in recipient countries. Materials are not sourced locally, labour is Chinese, and consequently, these projects come at environmental expense. A dedicated BRI department would take local capabilities into account.

Doubtless, the BRI has brought vital infrastructure and interconnectedness to developing countries. But for the next phase, China should ensure economic viability of projects have ostensible immediate benefits for the recipient countries. Yes, if you teach a man to fish you feed him for a lifetime – but if you don’t give him a fish in the meantime, he’ll starve.

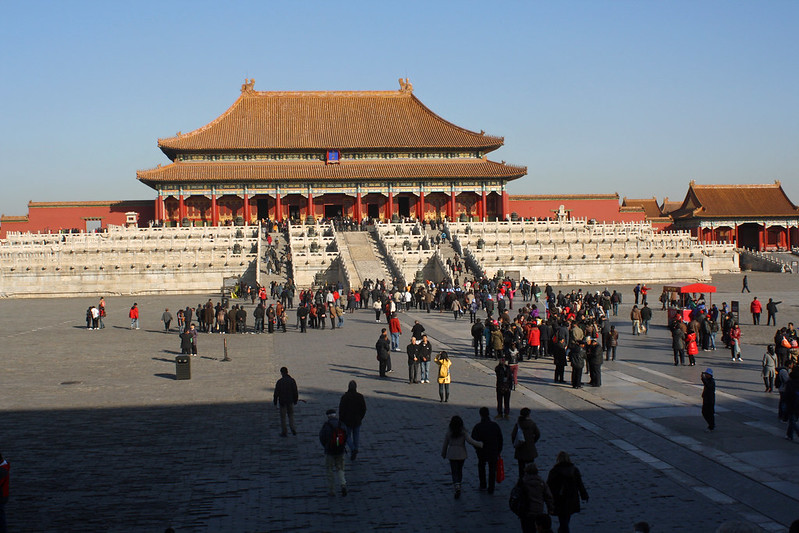

“Beijing” by Ib Aarmo is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.